Voter Mobilization Strategies

Social movements are more likely to secure wins when there are more Democrats and progressive allies in office.[1] The vast majority of campaigns also rely both directly and indirectly on elected officials, policies, and ballot propositions in order to secure wins. Even organizations that claim to work “outside the system” see much more success in areas with liberal voters and policymakers. Establishing a large base of progressive voters who will approve progressive policies and elect progressive candidates is crucial to social movement success.

The most effective strategies for mobilizing progressive voters include:

- Work with established groups (if you can)

- Use evidence-based practices

- Prioritize personal interactions

- Avoid mobilizing the opposition

Work with established groups (if you can)

Voter mobilization in urban and suburban areas often requires high levels of expertise, funding, and coordination. If you are an individual with little voter mobilization experience, we recommend volunteering with an established voter mobilization group in order to have the most impact and build your knowledge and skills.

Many modern voter mobilization groups are run by and for low-income people, youth, people of color, and women in order to build grassroots power and fight for truly progressive and transformative policies and policymakers. Working with these groups can help you not only mobilize voters, but also build community resilience and empower marginalized groups.

Indivisible is an organization working to build progressive voting power to combat the Trump administration. The people who formed Indivisible were outraged to watch a small number of conservatives take control of the U.S. political system, and for Trump to win the presidency despite losing the popular vote. Indivisible has organizing groups and voter mobilization volunteer opportunities across the country working to benefit progressive causes. Learn how you can get involved by visiting the Indivisible website, available at: https://www.indivisible.org/

If you live in California, Power California (made up of the former organizations YVote and Mobilize the Immigrant Vote) is one of the most effective and progressive coalitions engaged in youth organizing and voter mobilization work. Power California is made up of youth organizations from all across California and has registered over 40,000 young people since 2016. You can contact them to see how you can get involved by visiting their website, available at: https://powercalifornia.org/

If these groups do not have opportunities where you live, HeadCount offers an excellent list of organizations across the U.S. that mobilize voters, protect voters’ rights, conduct research, and produce civic technology. You can browse their list of organizations to see where you can get involved by visiting their website, available at: https://www.headcount.org/organizations/

Finally, if you live in an area with no voter mobilization groups at all, you can work on your own to help build progressive community voter power. In 2018, Dr. Veronica Terriquez helped create the Central Valley Freedom Summer project, which trained 25 college students who grew up in the Central Valley on how to mobilize low-income, youth, and voters of color in their largely rural hometowns. Because voter turnout is historically very low in these communities, it is expected that the small number of students mobilizing youth will have a large impact. The Central Valley Freedom Summer project will not have statistics on its effectiveness until after the 2018 elections, but you can follow the project on its Facebook page in order to receive upcoming articles on the most effective tactics and strategies for using grassroots voter mobilization strategies, available at: https://www.facebook.com/CVFS2018/

Use evidence-based practices

For those who are interested in running their own voter mobilization campaigns, it is important to follow the hundreds of scientific studies on effective mobilization strategies, not conventional methods or even the advice of professional “mobilization experts.” Many of the most widely used voter mobilization strategies—pre-recorded phone calls, synergy methods that contact voters in a variety of ways, distributing non-partisan voting information, email campaigns, and online advertising—have been shown numerous times by rigorous experiments to have little to no effect on voters.[2]

Green and Gerber have been publishing books summarizing all of the available research on voter mobilization for years. Their most current book, Get Out the Vote: How to Increase Voter Turnout, was published in 2015. They summarize hundreds of experiments on voter mobilization to offer a comprehensive and accurate list of best practices. They also examine the cost-effectiveness of each strategy and offer detailed explanations for how to choose strategies based on your local political environment. We summarize their findings below, but we recommend reading the most current edition of their book if you are planning on conducting a voter mobilization campaign.

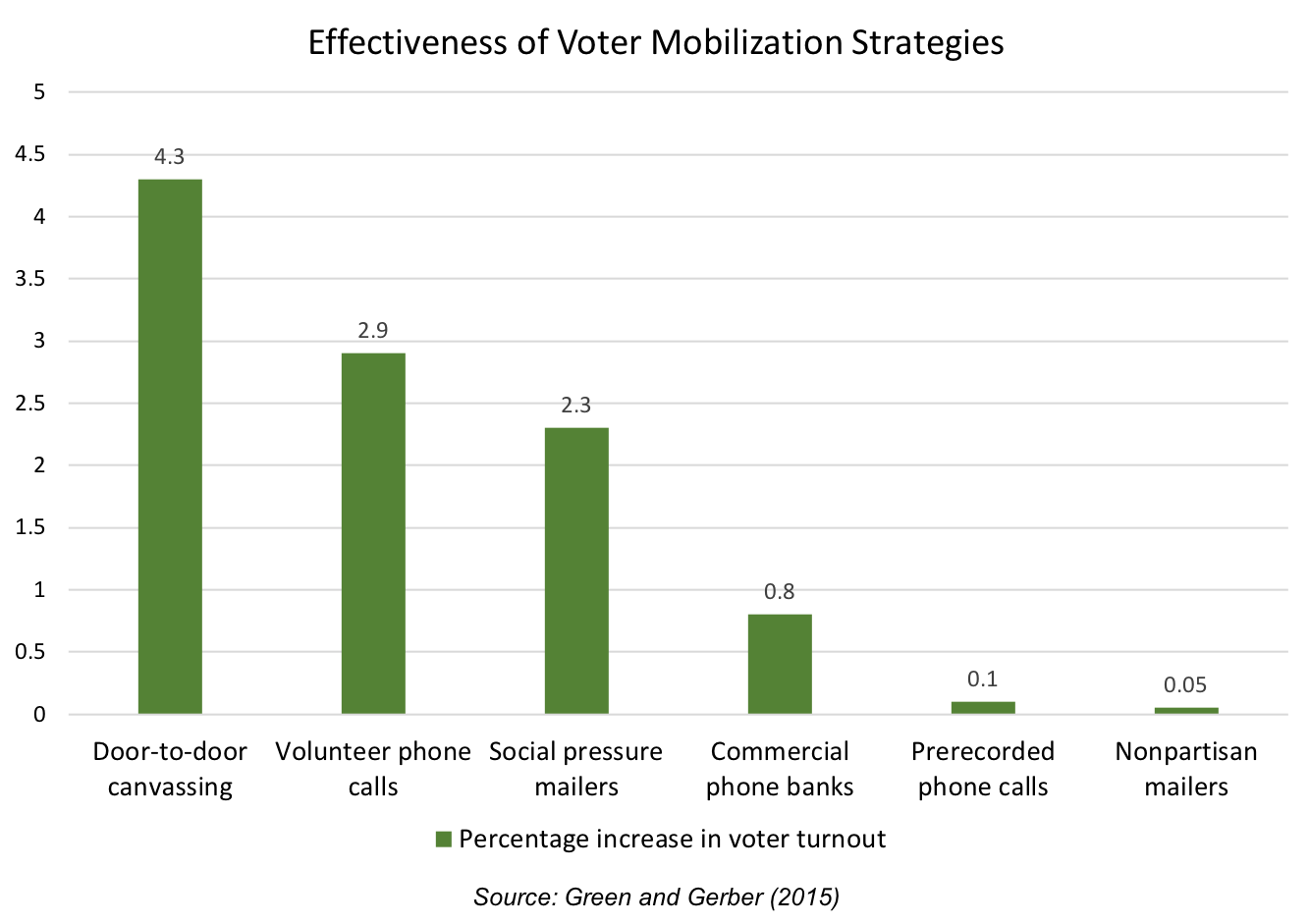

By pooling the findings from all experiments on voter mobilization, Green and Gerber (2015) were able to run meta-analyses to determine the average effect of each voter mobilization strategy. They found that door-to-door canvassing is the most effective, raising voter turnout by an average of 4.3%. Volunteer phone calls are the next most effective, raising turnout by 2.9%. Direct mail that prints the names of individuals who have not voted—called social pressure mailers—is slightly less effective than volunteer calls with an average effect of 2.3%.

As previously stated, nonpartisan mailers are not very effective (they only raise turnout by an average of .05%), nor are commercial phone banks (0.8%) or prerecorded phone calls (0.1%).

Some recent research has also shown promising results for text message reminders to vote.[3]

Your context will help determine the best strategy for you to use, but these findings are very promising for local activists—you can make a huge impact in progressive politics by simply talking with your neighbors through door-to-door canvassing and phone calls. Depending on the state of your local voter mobilization infrastructure, you may wish to volunteer with a local organization using best practices to mobilize progressive voters, or start your own door-to-door campaign.

Prioritize personal interactions

Overall, the more personal the interaction is between the voter mobilization campaign and the individual, the higher the chances are that the person will vote.[4] Green and Gerber (2015) contend that door-to-door canvassing is the “gold standard,” boasting the highest turnout rates. Because research has shown that local canvassers with community ties can be much more successful at boosting voting rates than distant outsiders,[5] progressive individuals can make a big impact in local politics through door-to-door canvassing, even in areas without formal voter mobilization groups. Phone calls from volunteers can also be effective when they are personal and unhurried.[6]

Voter mobilization messages should highlight positive norms that show the large number of progressives, youth, and people of color expected to turn out to vote. Studies have shown that emphasizing high expected turnout rates boosts voter turnout,[7] while lamenting low turnout rates can actually reduce turnout by 1.2 percentage points.[8]

Additionally, focusing on collective identities by using messaging encouraging people to “be a voter” is more effective at boosting turnout than simply asking people to vote.[9]

Overall, making personal contact that makes people feel wanted and needed at the polls is what makes people turn out to vote.[10]

Avoid mobilizing the opposition

In highly conservative cities, untargeted, non-partisan voter mobilization may simply increase the ranks of conservative voters without impacting progressive voter rolls much. Progressive change-makers can target their door-to-door canvassing efforts in local neighborhoods known to have progressive leanings and historically low voting rates.

Activists may also consider using persuasive campaigns, which seek to convince voters to vote for certain candidates or policies, instead of generally boosting turnout overall. Gerber and Green (2015) have also analyzed the effectiveness of these strategies. Appeals to urge ideologically aligned voters to vote in a certain way have been shown to successfully impact voting behavior. For example, activists can urge historically liberal voters to approve a certain progressive ballot proposition or vote for a certain progressive candidate.

Again, impersonal pre-recorded calls and online contact hasn’t been shown to be very impactful for persuasive campaigns.[11] Heavy advertisements and mobilization efforts from special interest groups—groups attempting to shift public policy in favor of their particular issue—have been shown to be risky moves. While some Democratic voters may view liberal special interest groups in a positive light, many view special interest groups as biased and manipulative. The research shows that special interest groups can significantly raise opposition from conservatives, canceling out or even overcoming the effect on progressive voters.[12]

TV advertising for persuasive campaigns seems to have very strong effects, but these effects only last about a week, so their timing must be planned carefully.[13] Contrary to widespread belief, reviews and meta-analyses examining a total of tens of thousands of voters show that negative political ads that attack opponents are not particularly effective.[14] They do reduce support for the target, but they also reduce support for the attacker.[15] Progressives should not waste money on smear campaigns against conservatives, and should instead prioritize building the progressive voter base.

NEXT SECTION: Assessing Your Tactical Repertoire

[1] Amenta, Caren, Chiarello, and Su 2010; Baumgartner and Mahoney 2005; Cress and Snow 2000; Giugni 2007; King, Bentele, and Soule 2007; Minkoff 1997; Soule and Olzak 2004

[2] Green and Gerber 2015

[3] Bhatti, Dahlgaard, Hansen, and Hansen 2017; Dale and Strauss 2009

[4] Green and Gerber 2015

[5] Sinclair, McConnell, and Michelson 2013

[6] Green and Gerber 2015

[7] Gerber and Rogers 2009

[8] Keane and Nickerson 2015

[9] Bryan, Walton, Rogers and Dweck 2011

[10] Green and Gerber 2015

[11] Green and Gerber 2015

[12] Green and Gerber 2015

[13] Gerber and Green 2015

[14] Lau and Rovner 2009; Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner 2007

[15] Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner 2007

Need to dig more into the literature? Visit our full references page to search for the article you’re interested in.