Learning from Successful Movements

Our research identified several overarching themes that make activism effective. How can you take an effective approach to your activism work?

Learning about the history of social movements is a great place to start. Which progressive social movements have been successful in securing change, and which have failed? Numerous scientific studies have examined which factors make social movements the most successful. Researchers have pooled decades of data on dozens of movements in order to determine, overall, how to create the most progressive change.

Thankfully, the research has shown that progressive social movements have been enormously successful in shaping policies, norms, and institutions to secure rights and freedoms for people, animals, and the environment.[1] We can learn from the successes of prior movements to ensure our own activism is effective and increase our chances of successfully creating change.

The most effective strategies for social movements overall include:

- Organize in a friendly political climate

- Mobilize frequently

- Choose nonviolent tactics

Organize in a friendly political climate

Social movements don’t secure wins out of thin air. Activists have been the most successful when they’ve organized in a favorable political climate. You will be the most likely to secure progressive gains when there is little to no opposition to your movement,[2] when the public supports your cause,[3] and when there are more Democrats and progressive allies in office.[4] All of these factors will tip the scales in your favor. Without allies or support, or in the face of extreme opposition, you will have a very difficult time getting your demands met, even if your demands aren’t directly related to policy.

If you don’t currently have support from the public or from elected officials, remember that you are an activist—your work is creating change! You can help create a more favorable climate for yourself. Almost all of the tactics listed in the Effective Activist guide can help shift public opinion in favor of progressive causes, but reading about how to recruit activists to your movement, how to develop effective messaging strategies, and how to effectively protest are good places to start. Our voter mobilization section is a good resource for ensuring more Democrats will be in office to vote in favor of your movement. You can also read up on how to influence elected officials to help you secure powerful allies.

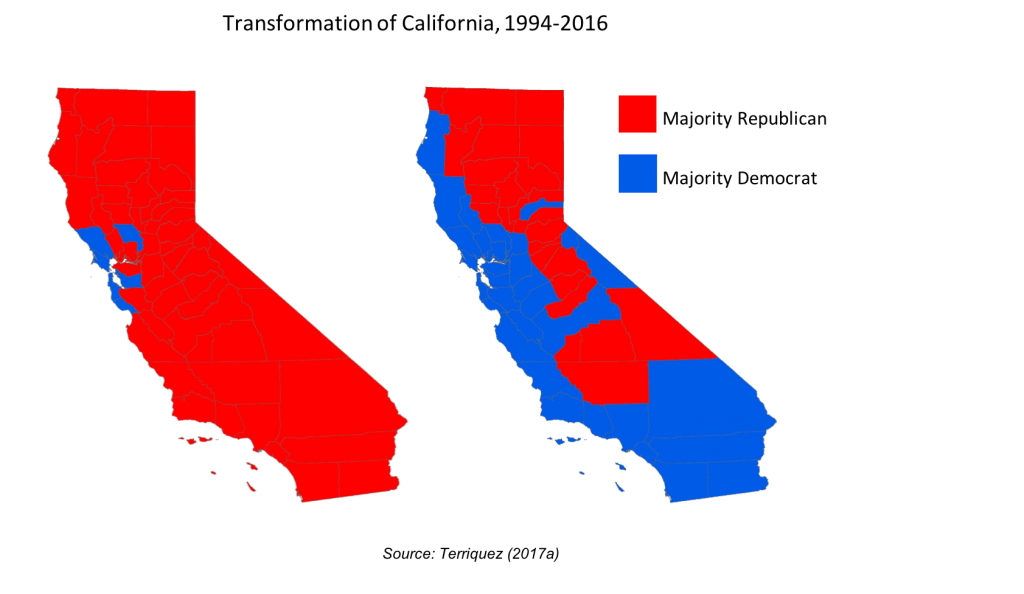

California is an excellent case study for activists to examine. California is currently one of the most liberal states in the U.S. and is often at the forefront of progressive change. Many activists take California’s progressive political climate and actions for granted, however. Dr. Veronica Terriquez, a leading expert on activism, has examined California’s progressive history. In the 1990s, California’s voters were largely Republican and passed a number of harmful propositions that hurt communities of color and immigrants. By 2016, however, California had transformed into a largely Democratic state, with 4 million more votes cast for Hillary Clinton than for Donald Trump.[5] The state is also currently resisting many of the oppressive policies of the Trump administration.

Terriquez notes that this change was largely due to grassroots organizing and voter mobilization, often carried out by youth and student leaders. Their work to mobilize marginalized communities, fight for community health and equality, and empower youth has not only led to a more progressive voter base and policy climate, it has also shifted the norms in California. Indeed, one study found that around half of the growth in acceptance of same-sex marriage in California is due to cohort effects,[6] meaning that young people are growing up in a more progressive climate and being socialized to norms of equality and social justice.

What does this mean for activists? Organizing work builds on itself, creating more favorable climates that make future activists more likely to succeed. If you live in a progressive area, maintaining activist infrastructure is key to continuing the forward march of social change. If you live in a highly conservative area, do not give up. Continue organizing so the next generation will be better equipped to help equality and justice flourish.

Mobilize frequently

Research has shown time and time again that frequent mobilization—protests, boycotts, sit-ins, petitioning, testifying, civil disobedience, and more—leads to social change.[7] Staying at the forefront of people’s minds and on the front page is crucial for long-term sustainability and success. Do not doubt the power of mobilizing!

One study on sit-ins in the U.S. South in the 1960s, in which people of color sat at segregated lunch counters to protest racial segregation, showed that cities with a sit-in were five times more likely to adopt desegregation policies. Even cities that did not have sit-ins themselves, but were nearby a city with a sit-in demonstration, were more likely to desegregate.[8]

Research on the U.S. environmental movement found that every protest increased the likelihood of pro-environmental legislation being passed by 1.2%.[9] Another study found that congressional districts that had 50 minority protests over the course of two years were 5% more likely to have their Congress members vote in support of minority issues.[10] Another found that issues that had an above average number of protests experienced a 70% increase in congressional hearings on the issue.[11] Each of these examples clearly demonstrates the impact of mobilization. It’s difficult for elected officials to ignore or dismiss large numbers of people in the streets.

It’s important to note that policymakers are more influenced by protests that include follow-up events and activities than they are by one-time protests.[12] Put simply, short-term mobilization has short-term impact. Infrequent mobilization allows the public to forget about your cause—out of sight, out of mind. In order to hold officials accountable, activists must continually demonstrate the importance of their cause. High-visibility movements are able to sway norms and shift public opinion by showing that people care deeply about the issue, and can even motivate and inspire others to take up activism later on.[13] Be sure to follow the best practices for protesting and boycotting most effectively, and then get out and mobilize.

Choose nonviolent tactics

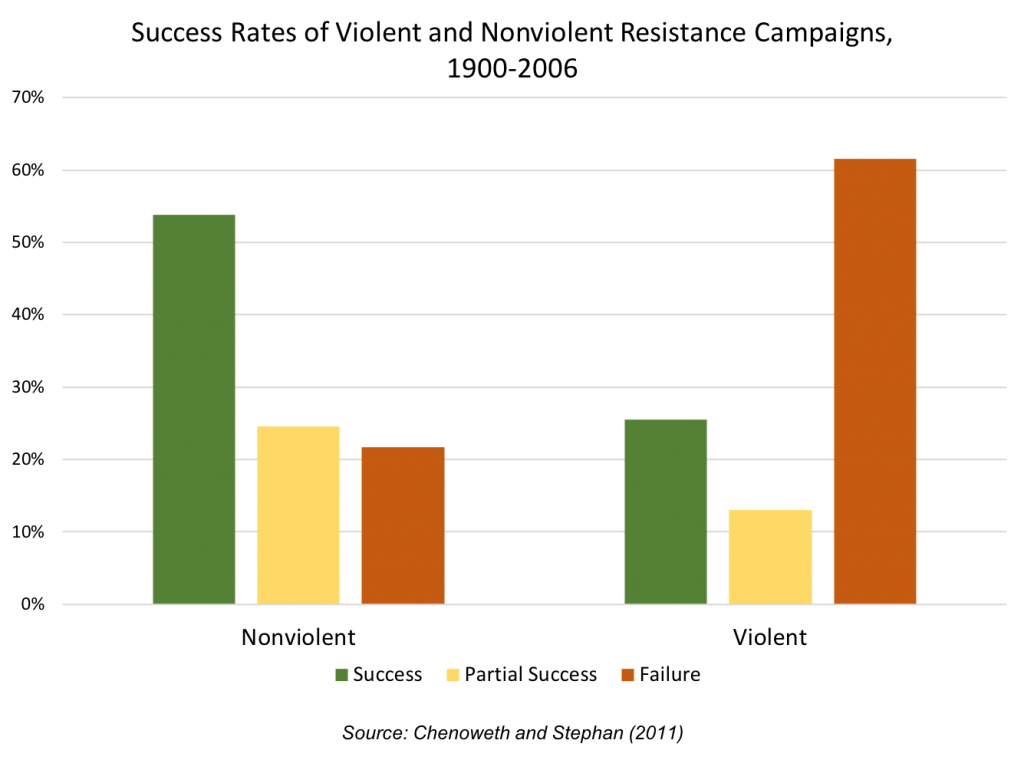

Some activists have turned to violent tactics out of frustration with the sometimes slow pace of change nonviolent campaigns achieve. While some activists mistakenly believe that extreme and violent tactics are more effective at achieving radical goals,[14] research has disproved this myth.

Chenoweth and Stephan’s 2011 book, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, is of the largest studies to examine the effects of nonviolent and violent social movements. They investigated 323 resistance campaigns around the world between 1900 and 2006 and found that, overall, nonviolent campaigns are two times as effective as violent ones at achieving their stated goals. Around 80% of nonviolent campaigns have been partially or completely successful, as compared to around 40% of violent campaigns. Even when only comparing to successful violent campaigns, nonviolent campaigns are more likely to create more durable and internally peaceful democracies with lower probabilities for relapsing into civil war.

Chenoweth and Stephan found that these barriers substantially impact the size of movements. The average nonviolent campaign has 200,000 members, as compared to 50,000 members for the average violent campaign. Although obtaining more supporters slightly increases the success rate of violent campaigns, it does not outweigh the disadvantages of their tactics. When considering only the top 20 largest campaigns (all of which had over 300,000 members), 70% of nonviolent campaigns were successful, as compared to only 40% of violent campaigns. Overall, their research shows that nonviolent tactics are much more effective.

Other recent research has also shown that extreme and violent tactics—including property damage, harming living beings, illegal tactics, and inciting violence—may not only be ineffective, but can actually produce a backlash effect and hurt social movements, making them even less likely to achieve their goals than if they had not mobilized at all.[15] Violent campaigns can also sometimes reinforce loyalty and obedience to the regime being challenged.[16]

Although extreme and violent tactics may have been more effective in decades past,[17] when policymakers were less responsive to social movements, today it is largely accepted that groups can achieve human, animal, and environmental rights through nonviolent protest. Thus, violent and extreme tactics are overwhelmingly seen as unnecessary and can reduce public support and push away political allies.

One study exposed individuals to different versions of animal rights, Black Lives Matter, and anti-Trump protests. Some people read vignettes of fictitious protests that damaged property, incited violence, and broke the law, while others read about protests that were more moderate. Interestingly, activists predicted that the violent protests would be more effective at increasing public support. In reality, individuals who were exposed to the violent protests supported the progressive social movements less than they did before seeing the protests. In contrast, moderate and nonviolent protests increased support for these social movements.[18]

In another study, elected officials who were shown fictitious violent protests in which activists broke shop windows and were pushing and pulling each other were less likely to view the protest issue as salient, less likely to support the issue, and less likely to take action on the issue. Again, nonviolent protests had the opposite effect and led to an increase in support by elected officials.[19]

One study even found that areas in the 1960s that had violent protests were more likely to vote Republican (as compared to areas with nonviolent protests, which led to more Democratic voting). The author hypothesizes that this impact was so great that violent protests may have tipped the 1968 presidential election from Hubert Humphrey to Richard Nixon.[20]

The combined findings of these studies may be surprising to those activists who have become disillusioned with nonviolent tactics. It is important to remember that nonviolence does not only work through “changing hearts and minds”—nonviolent campaigns are highly effective at imposing costly sanctions on opponents and are much more likely to result in strategic gains and regime change.[21] If you feel passionate and urgent about ramping up your impact, using violent tactics will actually make you less likely to succeed. You would do better to follow the numerous recommendations in this Effective Activist guide, which will help you boost the effectiveness of your campaigns and increase your likelihood of success as an activist.

Work will need to be done to bridge divides in activist communities and bring radicals currently pursuing violent tactics into the fold. Just because you, reading this guide, now know that nonviolent methods help achieve the most radical wins, does not mean that all other activists are aware of this. How can you engage in dialogue with activists who use different tactics in order to ensure your movement includes everyone in your community? Can you come to a compromise where you agree to fight for a more radical outcome—more social change that benefits the most marginalized—while using nonviolent tactics?

Now that you understand the factors that best set you up for success, you’re ready to learn how to make change. Let’s dive into the components of effective activism.

NEXT SECTION: Components of Effective Activism

[1] Agone 2007; Amenta, Caren, Chiarello, and Su 2010; Amenta, Caren, and Olasky 2005; Andrews 2001; Baumgartner and Mahoney 2005; Biggs and Andrews 2015; Cress and Snow 2000; Gamson 1990; Ganz 2000; Johnson, Agone, and McCarthy 2010; Soule and Olzak 2004

[2] Biggs and Andrews 2015; Soule and Olzak 2004

[3] Agone 2007; Amenta, Caren, Chiarello, and Su 2010; Biggs and Andrews 2015; Giugni 2007; Soule and Olzak 2004

[4] Amenta, Caren, Chiarello, and Su 2010; Baumgartner and Mahoney 2005; Cress and Snow 2000; Giugni 2007; King, Bentele, and Soule 2007; Minkoff 1997; Soule and Olzak 2004

[5] The New York Times 2017

[6] Lewis and Gossett 2008

[7] Agone 2007; Biggs and Andrews 2015; Cress and Snow 2000; Gamson 1990; Gillion 2012; Giugni 2007; Johnson, Agone, and McCarthy 2010; King, Bentele, and Soule 2007; King and Soule 2007; Minkoff 1997; Olzak and Soule 2009; Wasow 2017

[8] Biggs and Andrews 2015

[9] Agone 2007

[10] Gillion 2012

[11] King, Bentele, and Soule 2007

[12] Wouters and Walgrave 2017

[13] Taylor, Kimport, Van Dyke, and Andersen 2009

[14] Feinberg, Willer, and Kovacheff 2017

[15] Cress and Snow 2000; Feinberg, Willer, and Kovacheff 2017; Wasow 2017; Wouters and Walgrave 2017

[16] Chenoweth and Stephan 2011

[17] Chenoweth and Stephan 2011; Gamson 1990

[18] Feinberg, Willer, and Kovacheff 2017

[19] Wouters and Walgrave 2017

[20] Wasow 2017

[21] Chenoweth and Stephan 2011; Luders 2006; Morris 1999

Need to dig more into the literature? Visit our full references page to search for the article you’re interested in.